1. Importance of Fire Alarm Systems

1. Purpose and Importance

The primary mission of a fire alarm system is to protect life and property. Unlike other low-voltage systems, fire alarm systems require extra reliability measures to ensure they remain operational during emergencies.

- Detection: Identifies smoke, heat, and carbon monoxide.

- Alerting: Notifies occupants and local fire departments.

- Facilitation: Guides people to safety (e.g., via emergency lighting) and aids fire suppression (e.g., via smoke exhaust ventilation).

- Redundancy: Includes backup batteries within the Fire Alarm Control Unit (FACU) to operate during primary power failures.

2. Standards and Regulations

Compliance is mandatory and governed by several key organizations and codes:

- NFPA (National Fire Protection Association): Provides standards for design, wiring, and installation.

- NEC (National Electric Code) - Article 760: Focuses specifically on the installation of wiring and equipment for fire alarm circuits.

- AHJ (Authority Having Jurisdiction): The local entity that enforces rules. Their regulations can be stricter than manufacturer minimums or national codes.

- ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act): Ensures systems are accessible to all, including:

- Visual: Strobe lights for the hearing impaired.

- Audible: Alarms must be at least 15 decibels above average ambient noise for the visually impaired.

- Physical: Pull boxes must be reachable for wheelchair users.

3. Key Installation Guidelines

To ensure safety and prevent interference with building operations, specific technical rules apply:

- Support: Cables and conductors must be supported by the building structure, not left hanging as obstacles.

- Maintenance: Abandoned cables must be removed if accessible.

- Identification: Circuits must be clearly labeled at terminals and junctions to prevent accidental triggers during servicing or testing.

2. Different Systems For different Spaces

Types of Fire Alarm Systems

While all fire alarm systems share the same goal of safety, they vary significantly in complexity and wiring based on the building type. They are generally divided into three categories:

1. Basic Fire Alarm Systems

- Application: Typical small residential settings (homes).

- Key Feature: Technically not a "system" because it lacks a central control panel.

- Operation: Consists of standalone smoke, heat, or CO detectors.

- Connectivity: Modern versions are usually 120V AC powered with battery backups. They are interconnected (wired or wireless) so that if one alarm triggers, all alarms in the house sound simultaneously.

2. Conventional Fire Alarm Systems

- Application: Smaller commercial buildings like restaurants or schools.

- Wiring: Uses a "spoke and hub" method where devices are wired back to a central panel.

- Organization: The building is divided into zones.

- Limitations: While the central panel can alert the fire department and identify which zone triggered the alarm, it cannot identify the specific device or the exact room where the danger was detected.

3. Addressable Fire Alarm Systems

- Application: High-rise buildings and large commercial spaces like malls or office complexes.

- Wiring: Highly efficient; all devices share a single circuit, requiring much less wiring than conventional systems.

- Key Advantage: Every individual device has its own "address."

- Precision: The system identifies the exact location and device type (e.g., "Smoke Detector, Room 402") that triggered the alarm, allowing for a much faster emergency response.

Summary Comparison Table

| Feature | Basic (Residential) | Conventional (Small Commercial) | Addressable (Large Commercial) |

| Control Panel | None | Central Panel | Central Panel |

| Identification | Whole House | By Zone | By Specific Device |

| Wiring Style | Interconnected | Spoke and Hub (to zones) | Single Loop (Addressable) |

| Best For | Houses/Apartments | Schools/Restaurants | Malls/High-rises |

3. Fire Alarm System Components

3.1 Sensors

1. Smoke Detectors

Smoke detection is the most common method for providing early warning. There are two primary technologies used to sense smoke particles:

Ionization Smoke Detectors

- Mechanism: Uses a small amount of radioactive material to ionize air between two oppositely charged plates, creating a continuous electrical current.

- Trigger: When smoke enters the chamber, it disrupts the flow of ions, causing the current to drop and triggering the alarm.

- Pros/Cons: These are generally less expensive and more sensitive to fast-flaming fires compared to photoelectric models.

Photoelectric Smoke Detectors

- Mechanism: Uses light-sensing technology. A light beam is aimed inside the device; when smoke enters, it scatters the light onto a sensor (or disrupts a beam).

- Application: Similar to the sensors used in elevator doors to detect obstructions.

Note: Smoke sensors are often duct-mounted within a building's HVAC ductwork (near air handlers) to monitor air circulating throughout the entire structure.

2. Heat Detectors

Heat detectors are used in environments where smoke detectors might cause false alarms (like kitchens or dusty areas).

- Fixed Temperature: Triggers when the room reaches a specific threshold temperature.

- Rate-of-Rise: Triggers if the temperature increases rapidly within a short period.

- Limitation: They generally trigger much later in the progression of a fire than smoke detectors.

3. Carbon Monoxide (CO) Detectors

These sensors detect the presence of CO, a colorless, odorless, and deadly gas.

- Trigger: Alarms sound when CO levels exceed a specific parts per million (ppm) threshold.

- Technology: Often uses biomimetic technology, featuring a gel that changes color as it absorbs CO, which then triggers the sensor.

Summary Table: Sensor Comparison

| Sensor Type | Detection Method | Main Advantage |

| Ionization | Electrical current disruption | Fast response to flaming fires; low cost. |

| Photoelectric | Light beam disruption/scattering | Effective for smoldering fires. |

| Heat | Temperature threshold or change rate | Reliable in dirty/smoky environments. |

| Carbon Monoxide | Parts per million (PPM) concentration | Detects poisonous gas, not just fire. |

Initiators

1. Audible and Visual Alerts

Alert mechanisms are designed to ensure that all occupants, regardless of physical ability, are notified of an emergency.

- Fire Alarm Bells: * Used to provide a loud, audible signal for evacuation.

- Requirement: Must be at least 15 decibels above the average ambient sound level of the area to ensure they are heard.

- Strobe Lights: * Essential for individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing.

- Placement Rules: * Must be visible from anywhere in the building.

- Must be spaced no more than 100 feet apart.

- Must be located within 15 feet of both ends of a hallway.

- Placement Rules: * Must be visible from anywhere in the building.

- Voice Announcements: * Provide pre-recorded spoken instructions.

- Benefit: Offers more clarity than a simple bell, guiding occupants on specific evacuation routes or informing them when it is safe to re-enter.

2. The Fire Alarm Control Unit (FACU)

The FACU is the "brain" of the entire commercial fire alarm system.

- Function: It receives signals from all sensors (input), initiates the alert mechanisms (output), and transmits signals to emergency responders.

- Interface: Features a display panel that provides critical data to first responders and trained personnel regarding the status and location of the fire.

- Reliability: As mentioned in previous sections, this unit contains the backup batteries that keep the system running during a power outage.

Summary Table: Alert Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Type | Key Requirement/Feature |

| Bells/Horns | Audible | +15 dB above ambient noise. |

| Strobes | Visual | Visible everywhere; 100ft max spacing. |

| Voice Eval | Audio | Provides specific instructions via pre-recorded clips. |

| FACU | System Brain | Coordinates sensors, alerts, and fire department signals. |

Alert Mechanisms

Manual Initiators

Unlike automatic sensors (smoke or heat detectors), manual initiators rely on human intervention when a fire or emergency is spotted.

1. Pull Stations

- Description: Typically a red box mounted on the wall with clear operating instructions.

- Placement Requirement: Must be located within 5 feet (152 cm) of every individual exit.

- Function: Once pulled, it signals the Fire Alarm Control Unit (FACU) to sound the alarm and contact the fire department.

2. Break Glass Stations

- Mechanism: To prevent accidental activation, these devices require the user to break a glass pane to access the emergency button or lever.

- Impact: Activating this station notifies the fire department immediately and alerts building occupants to evacuate.

3. Buttons

- Operation: A simple press-button mechanism used to activate the system.

- Result: Functions identically to pull stations by sounding the alarm and signaling emergency responders.

4. Emergency Exit Alarms

- Function: These are alarms integrated into emergency exit doors.

- Trigger: If these doors are opened during normal business hours, the alarm sounds to indicate an evacuation is in progress.

- Communication: Opening the door sends a signal to the FACU, alerting the local fire department that the building is being evacuated due to a potential fire.

Summary of Manual Initiators

| Device Type | Activation Method | Key Requirement/Location |

| Pull Station | Pulling a lever down | Within 5ft of every exit. |

| Break Glass | Breaking a protective pane | Used to prevent accidental triggers. |

| Buttons | Pressing a button | Simple, direct activation. |

| Exit Alarms | Opening an emergency door | Alerts the FACU of unauthorized/emergency exit use. |

3.2 Power Supply

1. Primary Power Sources

Commercial fire alarm systems rely on the building's main electrical service as their primary source. In North America, this typically involves AC power at 60 Hertz.

- Single-Phase Power: * Used when electricity requirements are relatively low (common in residences).

- Typically provides 120V service.

- Three-Phase Power: * Used in commercial and industrial settings to operate heavy machinery.

- Voltage service ranges from 120/208V to 277/480V.

2. Secondary (Backup) Power

Because fire alarm systems must be functional 100% of the time, secondary power sources are mandatory.

- Batteries: Usually housed within the Fire Alarm Control Unit (FACU), these provide power immediately if the primary building power fails.

- Redundancy: Codes ensure the system remains active during blackouts or electrical fires that cut the main power lines.

3. Critical Design & Wiring Rules

To prevent system failure, the NFPA and NEC enforce strict electrical design standards:

- No GFCI/AFCI: Commercial fire alarm systems cannot be connected to Ground-Fault Circuit Interrupter (GFCI) or Arc-Fault Circuit Interrupter (AFCI) circuits. This is because these safety breakers can "trip" and shut off power to the alarm system when it is needed most.

- Voltage Drop Calculations: On DC (Direct Current) circuits, voltage drops as current flows through each device in a series. Engineers must provide documented calculations for Notification Appliance Circuits (NAC) to ensure the last device on the line still has enough power to function.

Summary Table: Power Specifications

| Power Type | Description | Key Requirement |

| Primary (AC) | Building power (120V-480V) | Must be a dedicated circuit; No GFCI/AFCI. |

| Secondary (DC) | Battery Backup | Must take over immediately upon AC failure. |

| Circuit Design | Voltage Drop Analysis | Ensures sirens/strobes work at the end of long wire runs. |

Master Summary of the Course

You have now completed the introduction to commercial fire alarm systems! We have covered:

- Purpose & Codes: Protecting life/property via NFPA, NEC, and ADA.

- System Categories: Basic (Residential), Conventional (Zones), and Addressable (Specific).

- Input Sensors: Smoke (Ionization/Photoelectric), Heat, and CO detectors.

- Manual Initiators: Pull stations, break glass, and emergency exit alarms.

- Output Alerts: Bells (+15dB), Strobe spacing, and Voice announcements.

- The Brain: The Fire Alarm Control Unit (FACU).

- Power: Primary AC and secondary Battery backup with voltage drop safety.

3.3 Fire Suppression Mechanisms

1. Suppression Systems (Extinguishing the Fire)

Commercial systems use different methods to put out fires based on the building's contents.

- Automatic Sprinklers:

- Reality vs. Movies: Sprinklers are heat-activated, not smoke-activated. They trigger individually (one at a time) rather than all at once.

- Benefit: They use significantly less water than a fire hose, minimizing property damage while controlling the fire.

- Dry Chemical / Special Hazard Systems:

- Mechanism: Uses powders like sodium bicarbonate or monoammonium phosphate.

- Application: Ideal for areas where water would cause devastating damage (like server rooms or kitchens).

2. Emergency Lighting

Lighting is critical for preventing panic and ensuring a fast evacuation.

- Open Area Lighting: Illuminates large spaces (hallways/foyers) to reduce panic and show the general path to safety.

- Task Lighting: Specifically placed to help occupants perform safety actions, such as reading instructions on a fire extinguisher or operating an emergency exit handle.

3. Air Management (Smoke Control)

The fire alarm system communicates with the building’s HVAC and ventilation systems to manage smoke.

- Vents and Fans: Activated to exhaust smoke from the building, improving visibility for occupants and firefighters.

- Air Handlers: Equipped with duct sensors, these units can shut down or redirect airflow to prevent smoke from being pumped into unaffected parts of the building.

4. Elevators and Doors

The system controls the movement of mechanical components to contain the fire and protect people.

- Elevator Recall: Sensors in lobbies and equipment rooms ensure elevators do not open their doors on a floor where smoke or fire is detected.

- Electromagnetic Doors: * High-traffic doors are often held open by electromagnets.

- When the alarm triggers, the magnets de-energize, allowing the doors to close automatically to create a fire barrier and prevent the spread of flames and smoke.

Summary Table: Suppression & Integration

| Mechanism | Primary Action | Key Benefit |

| Sprinklers | Heat-activated water release | Localized fire control; less water damage. |

| Dry Chemical | Specialized powder discharge | Fire suppression without water damage. |

| Air Handlers | Duct sensor-triggered shutdown | Prevents smoke circulation. |

| Mag-Doors | De-energizing magnets | Automatic containment of fire/smoke. |

| Elevators | Floor monitoring/recall | Prevents passengers from entering fire zones. |

3.4 Fire Alarm Control Unit

The Fire Alarm Control Unit (FACU)

The FACU is responsible for receiving signals from initiators (sensors/pull stations), processing them, and triggering the appropriate response (alarms/notification to authorities).

System Conditions (The Four States)

The annunciator (display panel) on the FACU indicates the current state of the system using four standardized conditions:

- Alarm Condition

- Meaning: An active, critical threat to life or property (e.g., smoke detected or a pull station activated).

- Action: Immediate evacuation of occupants and automatic dispatch of the fire department.

- Trouble Condition

- Meaning: A fault exists within the system's wiring or components (the system is "troubled").

- Causes: Often a "short" or an "open" circuit in the wiring, a disconnected device, or a failed communication line to the fire department.

- Action: Immediate maintenance is required to ensure the system works if a real fire occurs.

- Supervisory Condition

- Meaning: The system is functional, but a monitored building component is in an incorrect state.

- Example: A sprinkler valve is closed when it should be open, or a tamper switch has been triggered.

- Action: Investigate the specific equipment to return it to its required operating state.

- Normal Condition

- Meaning: All circuits, field devices, and wiring are functional.

- Action: No action required; the building is secure.

Summary Table: FACU Status Indicators

| Condition | Indicator Color (Typical) | Meaning | Priority |

| Alarm | Red | Emergency: Fire or smoke detected. | Highest |

| Supervisory | Yellow/Orange | Process Issue: Valve or switch in wrong position. | Medium |

| Trouble | Yellow/Orange | System Fault: Broken wire or technical failure. | Medium |

| Normal | Green | All Clear: System is fully operational. | Low |

'HVAC Fundamental (English) > Fundamental Full' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Electrical Installation (Full ver.) (0) | 2026.01.04 |

|---|---|

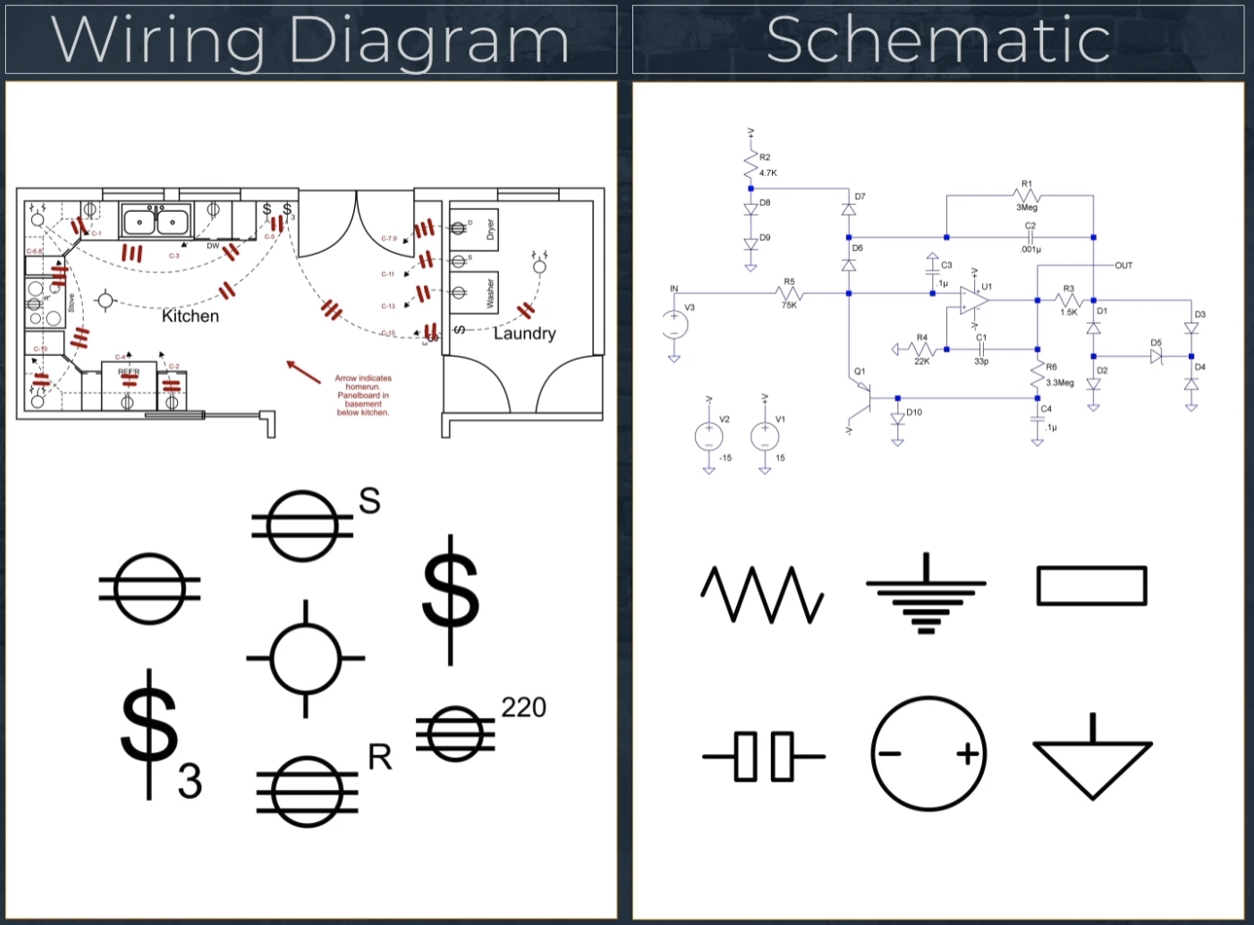

| Reading Schematics and Drawings (Full ver.) (0) | 2026.01.03 |

| Introduction to Refrigeration Systems (Full Ver.) (0) | 2026.01.02 |

| Temperature, Pressure, and Heat (Full ver.) (1) | 2025.12.29 |

| Residential HVAC Controls (Full ver.) (0) | 2025.12.27 |